Authors: John-Paul Swoboda KC and Rebecca Henshaw-Keene

In this article, John-Paul Swoboda KC and Rebecca Henshaw-Keene discuss the current iteration of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, which was introduced in the House of Commons in October 2024 by Kim Leadbeater (Labour MP for Spen Valley) and completed its passage through the House of Commons on 20 June 2025. It was introduced in the House of Lords on 23 June 2025 and is sponsored in the Lords by Lord Falconer of Thoroton (Labour).

We provide an overview of how the Bill is laid out, and give our thoughts on what we see as the potential contentious aspects of the Bill for personal injury and disease practitioners.

Overview

If passed onto the statute books, the Bill would allow terminally ill adults, subject to safeguards and protections, to choose to request and be provided with lawful assistance to end their own life. As currently drafted, the Bill applies to mentally competent adults (within the meaning of the Mental Capacity Act 2005), aged 18 and over, who are terminally ill and are in the final six months of their life.

The stated policy objectives are:

- To give adults who are already dying a choice over the manner of their death;

- For this choice to be part of a holistic approach to end-of-life care;

- To create a robust legal framework for this provision;

- To protect individuals from fear of and actual criminalisation where they provide such assistance in accordance with the provisions of the Bill.

The Bill was introduced on 5 September 2024, after the Private Members’ Bill Ballot. The Bill’s Second Reading was on 29 November 2024, meaning there was about 2 months to instruct a drafter to formulate the Bill.

The Government have since published Equality Impact Assessments and memoranda on human rights in June of this year.[1]

Background to the Act

At present it is a criminal offence to intentionally encourage or assist the suicide (or attempted suicide) of another person (Section 2(1) of the Suicide Act 1961).

Prosecutions under this offence are rare. In the 15 years up to 31 March 2024, 187 cases were referred to the CPS, of which 6 are ongoing.[2] A doctor commits no offence when treating a patient in a way which hastens death, if the purpose of the treatment is to relieve pain and suffering.

Conversely, a person who provides assistance to another in accordance with the Bill would not face any criminal (or civil) liability. The Section 2 offence would continue to apply to assistance falling outside the framework in the Bill.

The House of Lords and the Supreme Court have considered whether the present state of the law of England and Wales relating to assisting suicide infringes the European Convention on Human Rights (“the Convention”).

In R (Pretty) v Director of Public Prosecutions [2002] 1 AC 800, Mrs Pretty argued that the refusal of the Director of Public Prosecutions to grant her husband immunity from prosecution if he assisted her in killing herself and/or that the prohibition on assisting suicide in section 2 of the 1961 Act violated her rights under Articles 2, 3, 8, 9 and 14 of the Convention. The House of Lords held that her desire to end her life did not engage her rights under those Articles, and that Parliament had justified the existing law and the application of it.

Mrs Pretty was partially successful on appeal to the European Court of Human Rights (“the ECHR”). In Pretty v United Kingdom (2002) 35 EHRR 1, the ECHR found that her desire to end her life did engage Article 8.1. The ECHR has since gone on to find in subsequent cases that Article 8.1 encompasses the right to decide how and when to die, and in particular the right to avoid a distressing and undignified end to life (provided that the decision is made freely). [3]

However, interference with Mrs Pretty’s rights under Article 8.1 were justified by Section 2 of the Suicide Act 1961 which was “designed to safeguard life by protecting the weak and vulnerable and especially those who are not in a condition to take informed decisions against acts intended to end life or to assist in ending life”. The blanket ban on assisted suicide was not therefore disproportionate and the DPP had sufficient flexibility not to bring a prosecution. Interference in Mrs Pretty’s case was justified as necessary: both in a democratic society and for the protection of the rights of others.

In R (on the application of Nicklinson and another) (Appellants) v Ministry of Justice (Respondent) [2014] UKSC 38 (“Nicklinson”), a panel of nine Justices reconsidered the law’s compatibility with the Convention. It is a complex judgment. Of the five Justices who found the Court had a constitutional authority to make a declaration that the general prohibition on assisted suicide in Section 2 of the 1961 Act was incompatible with Article 8 of the Convention, only two Justices would have done so. Four Justices found that Parliament was inherently better qualified than the courts to assess these issues, and that under present circumstances the courts should respect Parliament’s assessment.

The Bill

Clause 2 defines a terminal illness as a progressive illness or disease that cannot be reversed by treatment and can reasonably be expected to lead to death within six months. The act of voluntarily stopping eating or drinking would not qualify a person as terminally ill under the Bill. A person would not be considered terminally ill only because they had a disability or mental disorder.

Clause 5 covers preliminary discussions about assisted dying. Whilst no registered medical practitioner is under any duty to raise the subject of the provision of assistance in accordance with this Act with a person, there is no prohibition on the medical practitioner exercising their judgment as to when it would be appropriate to do so. I.e., the subject of assisting dying need not be raised only by the terminally ill person.

Clauses 8 and 13 explain that the person who wishes to be provided with assistance to end their life must make two declarations. The first declaration is witnessed by the “coordinating doctor” who must then carry out an assessment under Clause 10. The coordinating doctor must have had training in assessing capacity, the potential for coercion, reasonable adjustments for autistic people and people with a learning disability, and domestic abuse.

The person must meet the following requirements at this stage:

(a) is terminally ill,

(b) has capacity to make the decision to end their own life,

(c) was aged 18 or over at the time the first declaration was made,

(d) is in England and Wales,

(e) is ordinarily resident in England and Wales and has been so resident for at least 12 months ending with the date of the first declaration,

(f) is registered as a patient with a general medical practice in England or Wales,

(g) has a clear, settled and informed wish to end their own life, and

(h) made the first declaration voluntarily and has not been coerced or pressured by any other person into making it.

If the coordinating doctor is satisfied that these requirements are met, the person must be referred to an ‘independent doctor’ who must assess the same requirements (save for those about residency).

Clause 12 sets out that both doctors must examine the person’s medical records and explain treatment options and any available palliative, hospice or other care that may be available, including symptom management and psychological support. They must also explain the process of administering the substance which will assist the person to end their own life. They must make referrals for assessment on diagnosis of the terminal illness or capacity if they are in any doubt.

Clause 16 sets out a referral to a multidisciplinary panel. The panel must hear from, and may question, the coordinating doctor and/or the independent doctor, and may hear from the individual. They may also question ‘any other person’. Any of this communication may take place on video link or audio link, including with the individual. There must be exceptional circumstances not to hear from the individual. Where the panel refuses to grant a certificate of eligibility in respect of the person, the person may appeal to the Voluntary Assisted Dying Commissioner. Such an application can only be made once. The Commissioner must hold (or have held) office as a judge of the Supreme Court, Court of Appeal, or High Court. The Bill does not include any provisions to appeal the decision of the Commissioner.

Clause 25 is entitled ‘Provision of assistance’ and sets out the provision of ‘approved substances’ directly to the individual. It says this:

(4) When providing a substance under subsection (2) the coordinating doctor must explain to the person that they do not have to go ahead and self-administer the substance and that they may still cancel their declaration.

….

(7) An approved substance may be provided to a person under subsection (2) by—

(a) preparing a device which will enable that person to self-administer the substance, and

(b) providing that person with the device.

In the case of an approved substance so provided, the reference in subsection (3) to the approved substance is to be read as a reference to the device.

(8) In respect of an approved substance which is provided to the person under subsection (2), the coordinating doctor may—

(a) prepare that substance for self-administration by that person, and

(b) assist that person to ingest or otherwise self-administer the substance.

(9) But the decision to self-administer the approved substance and the final act of doing so must be taken by the person to whom the substance has been provided.

(10) Subsection (8) does not authorise the coordinating doctor to administer an approved substance to another person with the intention of causing that person’s death.

Clause 22 mandates that the Secretary of State must appoint independent advocates to provide support and advocacy for people with a learning disability, a mental disorder (as under Section 1 of the Mental Health Act 1983) or autism, who are seeking to understand options around end of life care, including the possibility of requesting assistance to end their own life.

Discussion

There are a number of clauses which appear pertinent to personal injury lawyers.

The first is, of course, how terms in the Bill will be defined. The Bill seemingly imports the phrase “clear settled and informed” regarding the wish to end one’s own life from the DPP’s Policy for Prosecutors [4] but is otherwise undefined, either in the Bill or in that Policy.

Also preserved in the act is the concept of personal autonomy, as is seen in Clause 25 (10) above. Nicklinson provides some assistance in understanding what personal autonomy may mean in this context.Lord Neuberger commented that: “I believe that there may be considerable force in the contention that the answer, both in law and in morality, can best be found by reference to personal autonomy. … it seems to me that if the act which immediately causes the death is that of a third party that may be the wrong side of the line, whereas if the final act is that of the person himself, who carries it out pursuant to a voluntary, clear, settled and informed decision, that is the permissible side of the line.” [95].

Likewise, there was support in Nicklinson that a system whereby a judge or other independent assessor was satisfied in advance that someone has a voluntary, clear, settled and informed wish to die and for his or her suicide then to be organised in an open and professional way would arguably provide greater and more satisfactory protection for the vulnerable, than a system which involves a lawyer from the DPP’s office inquiring, after the event, whether the person who had killed himself or herself had such a wish.

Clause 31 (1) operates as a “conscience clause” stating that “No person is under any duty to participate in the provision of assistance in accordance with this Act”. Specific provisions in Clause 31 provide clarification for health professionals, but for no other class.

For personal injury and disease practitioners, an example of the advice required (although by no means a simple one) is a client who may meet the eligibility criteria of the Act and seeks to understand the impact this would have on their civil claim for damages both in life and in the ‘lost years’.

Clause 38 proposes an amendment to the Coroners and Justice Act 2009, excluding “a death caused by the self-administration by the deceased of an approved substance” from the definition of an “unnatural death”. Whilst a Coroner currently has a duty to investigate suicides as they are deemed “unnatural deaths”, they would have no duty to investigate assisted dying as a matter of course.

His Honour Judge Teague KC, former Chief Coroner, has commented: “The effect of cl 35(1) is thus to exclude assisted deaths from the posthumous judicial scrutiny that all other intentionally procured fatalities automatically attract. This represents a momentous change in the law of England and Wales. Even in the days of capital punishment, coroners were required to conduct inquests into deaths resulting from the lawful execution of judicial sentences.”[5]

As HHJ Teague KC has said, the multidisciplinary panels themselves will not be judicial bodies and cannot diminish the risk of wrongdoing at later stages in the process. The Coronial postmortem may be a definitive way of determining whether the diagnosis of terminal illness was a reasonable one, or that the requirements of Clause 25 were adhered to. This may become a significant issue: the Government’s impact assessment has estimated that by 2038 there will be over 7,000 applications under the Act, and almost 5,000 deaths a year. [6] Lord Falconer’s explanatory notes to the Lords state that nothing in this Clause prevents anyone from referring a death to the Coroner where they have concerns that the death has not occurred in line with the provisions of the Bill. Deaths which are not investigated by a coroner are instead scrutinised by a medical examiner.

A comparison can be made by the eligibility criteria in the Bill (above) and those proposed by Lord Wilson in Nicklinson at [205]. In the Bill, the ‘gateway’ provision appears to be the diagnosis of a terminal illness with a life expectancy of less than 6 months. Whilst those engaging with the individual under the Bill must explain to them appropriate palliative, hospice or other care, and offer to refer them to a practitioner who specialises in such care for the purpose of further discussion, Lord Wilson’s list of factors is arguably more holistic.

That being said, Clause 39 mandates the Secretary of State to provide a code of practice on the assessment of the individual’s intention to end their own life and on the information which is made available as mentioned in sections of the Bill on treatment or palliative, hospice or other care available to the individual.

Summary

The Bill has passed its second reading in the House of Lords. After the second reading the Bill goes to committee stage – where no doubt a detailed line by line examination and discussion of amendments will take place. It is therefore likely there will be more changes to the Bill before it is finalised.

These are our thoughts having read the Bill and some of the wide-ranging debates on this sensitive and complex topic. The Bill is not in its final form and all commentary is current as at 22.09.2025. We will update this blog with any major changes.

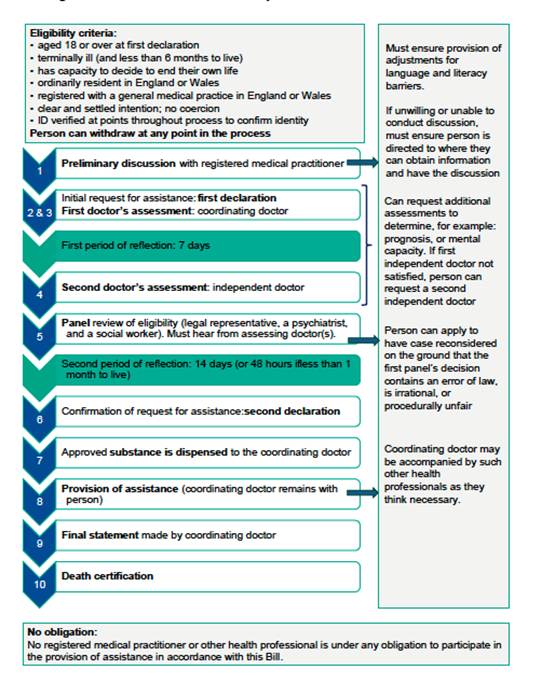

The following graphic may be useful.

Taken from the Government’s Impact Assessment dated 14.5.2025

[1] https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3774/publications

[2]Commons Library Research Briefing, 22 November 2024

[3] See the summary of the development of domestic and European jurisprudence in Lord Neuberger’s judgment in R (on the application of Nicklinson and another) (Appellants) v Ministry of Justice (Respondent) [2014] UKSC 38 (“Nicklinson”) at [21] – [43].

[4] https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/suicide-policy-prosecutors-respect-cases-encouraging-or-assisting-suicide

[5] “Assisted Dying and Coroners” New Law Journal 2 May 2025

[6] https://bills.parliament.uk/publications/61744/documents/6780